M. Kobe

Q4 featured artist

M. Kobe is a storyteller and artist from Baton Rouge, Louisiana. She holds an MFA in Painting from Boston University and both a BFA in Painting and a BA in Art History from Louisiana State University. Working primarily with textiles, found natural materials, and “lucky” objects, she draws upon her experiences growing up in the American South. Her work contends with the religious mythologies of her upbringing, superstition, notions of home, and cultural inheritance. Kobe’s work has been shown at Morgan Lehman Gallery (New York, NY), the University of Wisconsin-Green Bay (Green Bay, WI), Prince Street Gallery (New York, NY), and The Arrowmont Galleries (Knoxville and Gatlinburg, TN). Her most recent solo exhibition was at Cedar Crest College (Allentown, PA) and she has an upcoming exhibition at Walters State Community College (Morristown, TN).

She was an Artist-in-Residence at the Arrowmont School of Arts and Crafts. In 2024, Kobe spoke at the Mid-South Sculpture Conference on repurposed materials in sculpture. She was the grand prize recipient of the 2023 Esther B. and Albert S. Kahn Career Entry Award.

As an artist from the American South, primarily Louisiana and Tennessee, I make work that speaks to our fears of the dark, of death, of the unknown, questioning what it means to choose to live in these regions today. Drawing from the myths of my religious upbringing, folk tales, and country music, I navigate inherited superstition and write my own. My work functions as reminders of finitude, pointing to the urgency of the present, of living. The art objects I make, tapestries and sculptures, are embedded with found natural or "lucky" materials and imbued with personal narrative. Serving as desperate attempts at future prosperity, the forms in my work often resemble calendars, portals, and tombs. I am learning what it means to love a place that can be hard to love, to love a landscape that loves me back. I make my work with gratitude and admiration and as a critical yet redemptive response to the complicated places I call home.

Studio Practice

Much of my work has to do with where I call home - the people, places, and contexts that I situate myself in daily, where I’m from and where I choose to build a life. I have a home studio, and I appreciate how the line between my studio work and my home life blurs. I make my work in my studio, on the couch, in the kitchen, and in my backyard. I live with it. The materials I use are influenced by this - gravel from our driveway, pistachio shells from my lunches, clay collected in the woods behind our house, and animal hides gathered from local hunters. The scale of my work is often shaped by my space as well - tapestries as wide as my porch, my side of the bed, or the length of our house. Much of my work is very repetitive - adding together small components until they become larger than themselves (physically and conceptually). I usually start my days with more repetitive tasks like washing gravel, stitching or carving text, and painting shells. As I become more engrossed in my work, I shift my focus to larger moves - like building support structures, stitching large swaths of fabric together and wood working.

Collecting Tennessee red clay

Lake Douglas all dried up, TN

Home Studio

WIP in the drive way - thinking about camouflage

Inspiration

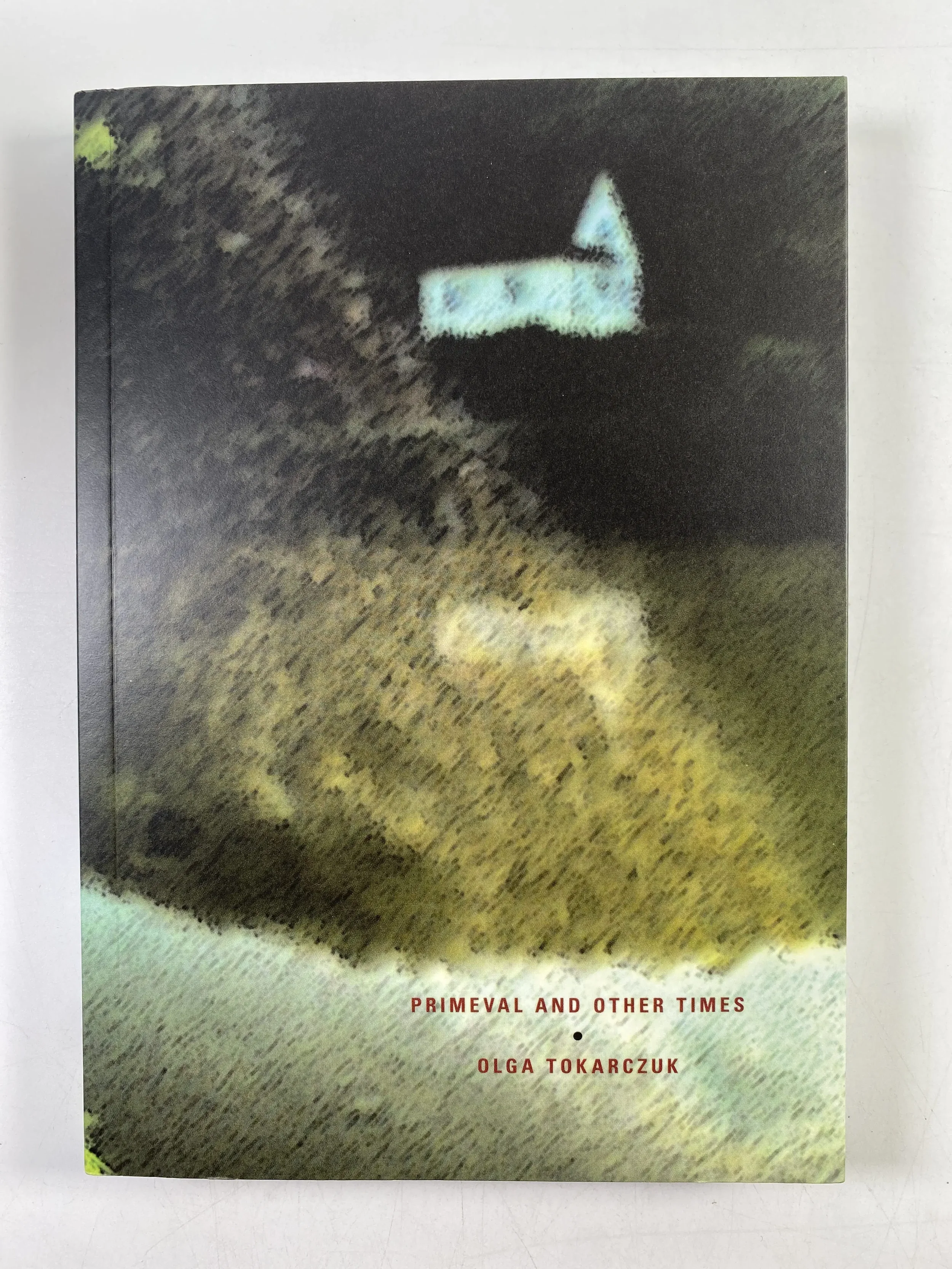

I think about artists like Kiki Smith, Agnes Martin, and Sally Mann - artists who are telling stories and who are connected to the act of making as if it were its own religion. I listen to musicians and read storytellers like Willie Carlisle, Abe Partridge, Tyler Childers, Barbara Kingsolver, and Olga Tokarczuk. I write. I’ve been exploring how my own writing can be transformed in conversation, through memory, by mirroring or reversing the text, through the act of stitching and carving and retelling the same stories over and over again, adding and taking away each time. Much like the way ballads are written, or poems. I look at the world around me and am constantly inspired by how marked surface and textures camouflage or confuse your understanding of an object and space. I saw this great installation in Western North Carolina at the Fields of the Wood. There are these large concrete block letters set into the side of a mountain - painted white. They’re physically heavy and visually heavier. There’s no escaping them. They transform a landscape that is monumental in its own right. An overpowering, desperate need drives the communication of a formidable, unmistakable message. Working with a similarly desperate, but different conceptual goal, I wonder how my work can transform a space or landscape in the same way. How can I make work that alludes to the stories I write? Or make work that contends with stories I’ve known and felt? How do I leap forward out of art history, using those who influence me most (artists, authors, musicians) and towards everything that could be next?

Frosted window pane

Rocks near Douglas Dam

My fiance at The Field of the Woods

Challenges

A good friend of mine, Scott Smith, read me this quote from a book on Frank Auerbach he stole from the public library. I’ve had it pinned to my studio wall for the past five years: “Drawing is not a mysterious activity. Drawing is making an image which expresses commitment and involvement. This only comes about after seemingly endless activity before the model or subject, rejecting time and time again ideas which are possible to preconceive. And, whether by scraping off or rubbing down, it’s always beginning again, making new images, destroying images that lie, discarding images that are dead. The only true guide in this search is the special relationship the artist has with the person or landscape from which he is working. Finally, in spite of all this activity of absorption and internalization, the images emerge in an atmosphere of freedom.” —Leon Kossoff Making my work is constant, even when I’m not physically working on it. I think about it, I look at it, I share in-progress photos with friends. I break down tasks into manageable bites—things I can do for 10–15 minutes while cooking. I sew alongside my fiancé while he plays video games. I watch kitschy old vampire movies and videos of quilters on YouTube. I appreciate how they talk about their tireless practices. Sometimes resting means just seeing the work in a different space—dragging it into the yard, pinning it up in the kitchen. Letting it sit when I don’t know the next move, or when the process feels endless. Most projects begin with a material or two, a form in mind, and a pattern to move forward with. I usually make it halfway before something disastrous happens—adhesives fail, wood cracks, or it just looks wrong. Then it’s my job to step back, assess what’s working and what isn’t, and meet the piece where it’s at. Then, I make the big moves that scare me. I shift things, remove adornments, rip stitches. I’m ruthless. I keep what I can and destroy the rest. Then I respond—adding, stitching, letting the form evolve with no fixed vision. Usually, I stop when it’s about 80% done. I live with it, show my fiancé, ask friends. I almost always do the opposite of what they suggest. Eventually, I either come to terms with it—or make a few small changes.

Wood split and my project cracked in half

My work up in my kitchen - so I can think

WIP out in the yard - so I can see

WIP out in the yard - detail

Its important to be uncomfortable in the studio. The blankness, or uncertainty, is the only place where something new can come out of. Its taken me a long time to become comfortable with making work that ranges in media - making sculptures, tapestries, and paintings all at once, and showing them all in the same shows. My work sometimes makes dramatic shifts, from year to year. It always circles back to itself - even if not for awhile. Robert Irwin speaks about this, and finishing his work in his biography Seeing is Forgetting the Name of the Thing One Sees. He writes of an insistence in our society to measure greatness by performance and that our interest in the past, in the resolution of our questions, is how we measure our renaissances. To Irwin, this performance, this wrapping up of things, is “somewhat inevitable, almost a mopping-up operation, merely a matter of time” (Weschler 90). He expresses that “I’m not antiperformance, but I find it very precarious for a culture only to be able to measure performance and never able to credit the questions themselves” (Weschler 90). He continues to write of the practical application of this philosophical quandary as it relates to his practice, as it relates to my practice. He says that for a time, he himself must perform the answers he finds to his questions. For a time. When he’s in the questioning stage, these performances are usually awkward and clumsy. They don’t quite add up. As he continues this performance, the kinks work themselves out; he may perform elegantly or exactingly. Then he's “off again” (Weschler 90). This often leaves behind a less refined performance record. There is not so much a right answer so much as there are answers, some of which are more convenient or workable than others - at any given time. I find my interests, aesthetically, materially, and philosophically, to be arrow straight, but I understand this isn't always the case when others view my work. I, knowing the potential complications this poses, could not care less. In my mind, there is plenty of time, the rest of my life, to perform these answers, should I desire it. I have time to make “art in the best sense of the word” (Weschler 90). I am much more interested in inquiry, abstract phenomena, in performance as a means to the next. The clunky and less elegant answers, I find, have infinite possibilities for growth.

Reflection

studio Image

Dead king snakes in the road I collected bones from

working on the porch

WIP while teaching a National Workshop at Arrowmont School of Arts and Crafts